At fleetster we have our own instance of GitLab and we rely a lot on GitLab CI/CD. Also our designers and QA guys use (and love) it, thanks to its advanced features.

GitLab CI/CD is a very powerful system of continuous integration (CI), with a lot of different features, and with every new release, new features land. It has very rich technical documentation, but it lacks a generic introduction for people who want to use it in an existing setup. A designer or a tester doesn’t need to know how to autoscale it with Kubernetes or the difference between an image or a service.

But still, they need to know what a pipeline is, and how to see a branch deployed to an environment. In this article therefore I will try to cover as many features as possible, highlighting how the end users can enjoy them; in the last months I explained such features to some members of our team, also developers: not everyone knows what continuous integration is or has used Gitlab CI/CD in a previous job.

If you want to know why continuous integration is important I suggest reading this article, while for finding the reasons for using Gitlab CI/CD specifically, I leave the job to GitLab itself.

Introduction

Every time developers change some code they save their changes in a commit. They can then push that commit to GitLab, so other developers can review the code.

GitLab will also start some work on that commit, if GitLab CI/CD has been configured. This work is executed by a runner. A runner is basically a server (it can be a lot of different things, also your PC, but we can simplify it as a server) that executes instructions listed in the .gitlab-ci.yml file, and reports the result back to GitLab itself, which will show it in his graphical interface.

When developers have finished implementing a new feature or a bugfix (activity that usual requires multiple commits), they can open a merge request, where other members of the team can comment on the code and on the implementation.

As we will see, designers and testers can also (and really should!) join this process, giving feedback and suggesting improvements, especially thanks to two features of GitLab CI: environments and artifacts.

CI/CD pipelines

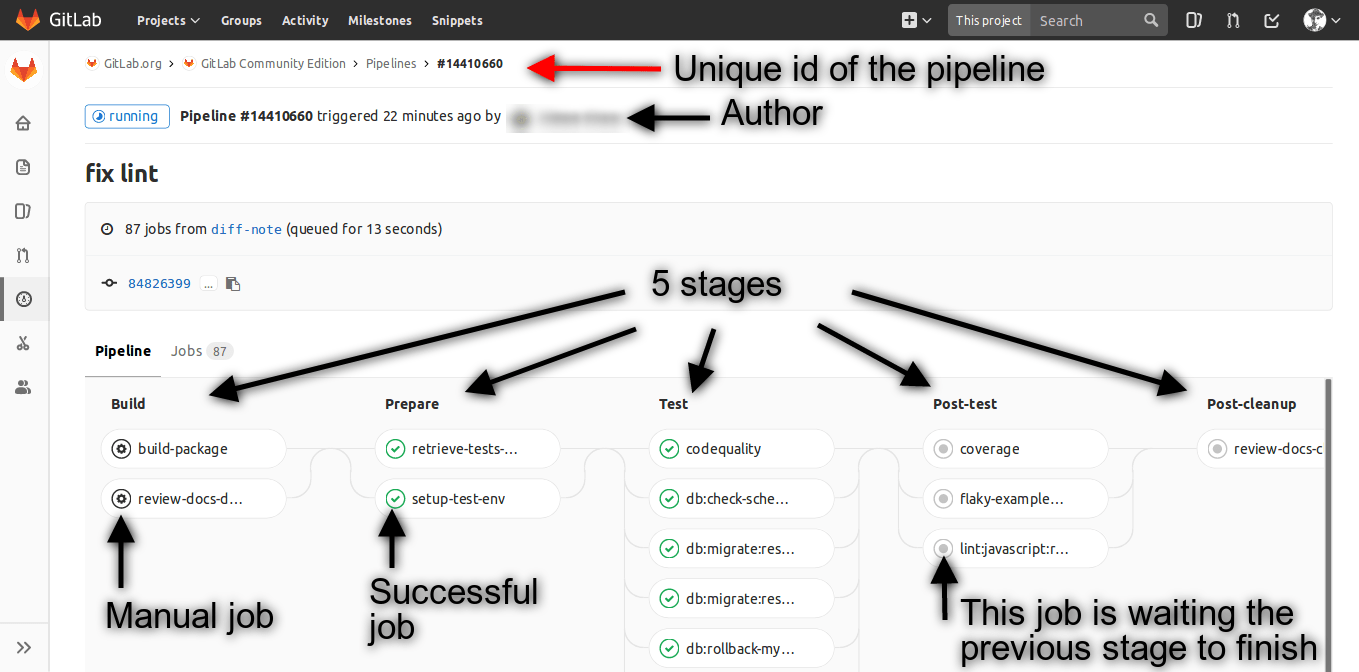

Every commit that is pushed to GitLab generates a pipeline attached to that commit. If multiple commits are pushed together the pipeline will be created for the last one only. A pipeline is a collection of jobs split in different stages.

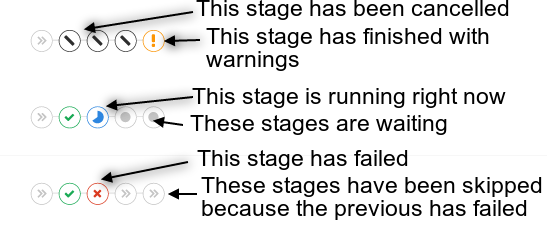

All the jobs in the same stage run concurrently (if there are enough runners) and the next stage begins only if all the jobs from the previous stage have finished with success.

As soon as a job fails, the entire pipeline fails. There is an exception for this, as we will see below: if a job is marked as manual, then a failure will not make the pipeline fail.

The stages are just a logical division between batches of jobs, where it doesn’t make sense to execute the next job if the previous failed. We can have a build stage, where all the jobs to build the application are executed, and a deploy stage, where the build application is deployed. Doesn’t make much sense to deploy something that failed to build, does it?

Every job shouldn’t have any dependency with any other job in the same stage, while they can expect results by jobs from a previous stage.

Let’s see how GitLab shows information about stages and stages’ status.

What is a CI job?

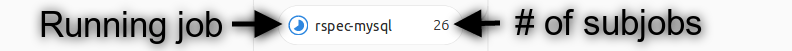

A job is a collection of instructions that a runner has to execute. You can see in real time what the output of the job is, so developers can understand why a job fails.

A job can be automatic, so it starts automatically when a commit is pushed, or manual. A manual job has to be triggered by someone manually. This can be useful, for example, to automate a deploy, but still to deploy only when someone manually approves it. There is a way to limit who can run a job, so only trustworthy people can deploy, to continue the example before.

A job can also build artifacts that users can download, like it creates an APK you can download and test on your device; in this way both designers and testers can download an application and test it without having to ask for help to developers.

Other than creating artifacts, a job can deploy an environment, usually reachable by an URL, where users can test the commit.

Job status are the same as stages status: indeed stages inherit theirs status from the jobs.

Artifacts

As we said, a job can create an artifact that users can download to test. It can be anything, like an application for Windows, an image generated by a PC, or an APK for Android.

So you are a designer, and the merge request has been assigned to you: you need to validate the implementation of the new design!

But how to do that?

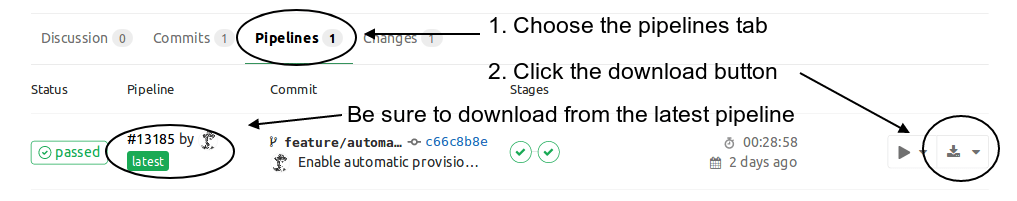

You need to open the merge request, and download the artifact, as shown in the figure.

Every pipeline collects all the artifacts from all the jobs, and every job can have multiple artifacts. When you click on the download button, a dropdown will appear where you can select which artifact you want. After the review, you can leave a comment on the MR.

You can also always download the artifacts from pipelines that do not have a merge request open ;-)

I am focusing on merge requests because usually that is where testers, designers, and shareholders in general enter the workflow.

But merge requests are not linked to pipelines: while they integrate nicely with one another, they do not have any relation.

CI/CD environments

In a similar way, a job can deploy something to an external server, so you can reach it through the merge request itself.

As you can see, the environment has a name and a link. Just by clicking the link you to go to a deployed version of your application (of course, if your team has set it up correctly).

You can also click on the name of the environment, because GitLab also has other cool features for environments, like monitoring.

Conclusion

This was a small introduction to some of the features of GitLab CI: it is very powerful, and using it in the right way allows all the team to use just one tool to go from planning to deploying. A lot of new features are introduced every month, so keep an eye on the GitLab blog.

For setting it up, or for more advanced features, take a look at the documentation.

In fleetster we use it not only for running tests, but also for having automatic versioning of the software and automatic deploys to testing environments. We have automated other jobs as well (building apps and publishing them on the Play Store and so on).

About the guest author

Riccardo is a university student and a part-time developer at fleetster. When not busy with university or work, he likes to contribute to open source projects.

An introduction to continuous integration was originally published on rpadovani.com.

Cover photo by Mike Tinnion on Unsplash