Software requirements change over time. Customers request more features and the application needs to scale well

to meet user demands. As software grows in size, so does its complexity, to the point where we might decide that it's

time to split the project up into smaller, cohesive components.

As we proceed to tackle this complexity we want to ensure that our CI/CD pipelines continue to validate

that all the pieces work correctly together.

There are two typical paths to splitting up software projects:

- Isolating independent modules within the same repository: For example, separating the UI from the backend,

the documentation from code, or extracting code into independent packages. - Extracting code into a separate repository: For example, extracting some generic logic into a library, or creating

independent microservices.

When we pick a path for splitting up the project, we should also adapt the CI/CD pipeline to match.

For the first path, GitLab CI/CD provides parent-child pipelines as a feature that helps manage complexity while keeping it all in a monorepo.

For the second path, multi-project pipelines

are the glue that helps ensure multiple separate repositories work together.

Let's look into how these two approaches differ, and understand how to best leverage them.

Parent-child pipelines

It can be challenging to maintain complex CI/CD pipeline configurations, especially when you need to coordinate many jobs that may relate

to different components, while at the same time keeping the pipeline efficient.

Let's imagine we have an app with all code in the same repository, but split into UI and backend components. A "one-size-fits-all" pipeline for this app probably would have all the jobs grouped into common stages that cover all the components. The default is to use build, test, and deploy stages.

Unfortunately, this could be a source of inefficiency because the UI and backend represent two separate tracks of the pipeline.

They each have their own independent requirements and structure and likely don't depend on each other.

The UI might not need the build stage at all, but it might instead need a system-test stage with jobs that test the app end-to-end.

Similarly, the UI jobs from system-test might not need to wait for backend jobs to complete.

Parent-child pipelines help here,

enabling you to extract cohesive parts of the pipeline into child pipelines that runs in isolation.

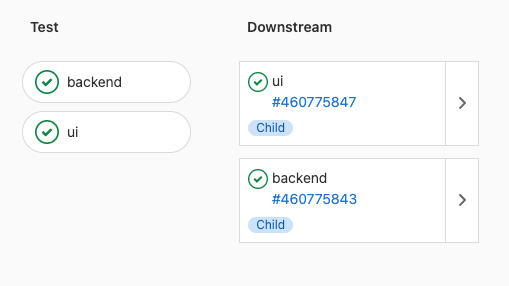

With parent-child pipelines we could break the configurations down into two separate

tracks by having two separate jobs trigger child pipelines:

- The

uijob triggers a child pipeline that runs all the UI jobs. - The

backendjob triggers a separate child pipeline that runs all the backend jobs.

ui:

trigger:

include: ui/.gitlab-ci.yml

strategy: depend

rules:

- changes: [ui/*]

backend:

trigger:

include: backend/.gitlab-ci.yml

strategy: depend

rules:

- changes: [backend/*]

The modifier strategy: depend, which is also available for multi-project pipelines, makes the trigger job reflect the status of the

downstream (child) pipeline and waits for it to complete. Without strategy: depend the trigger job succeeds immediately after creating the downstream pipeline.

Now the frontend and backend teams can manage their CI/CD configurations without impacting each other's pipelines. In addition to that, we can now explicitly visualize the two workflows.

The two pipelines run in isolation, so we can set variables or configuration in one without affecting the other. For example, we could use rules:changes or workflow:rules inside backend/.gitlab-ci.yml, but use something completely different in ui/.gitlab-ci.yml.

Child pipelines run in the same context of the parent pipeline, which is the combination of project, Git ref and commit SHA. Additionally, the child pipeline inherits some information from the parent pipeline, including Git push data like before_sha, target_sha, the related merge request, etc.

Having the same context ensures that the child pipeline can safely run as a sub-pipeline of the parent, but be in complete isolation.

A programming analogy to parent-child pipelines would be to break down long procedural code into smaller, single-purpose functions.

Multi-project pipelines

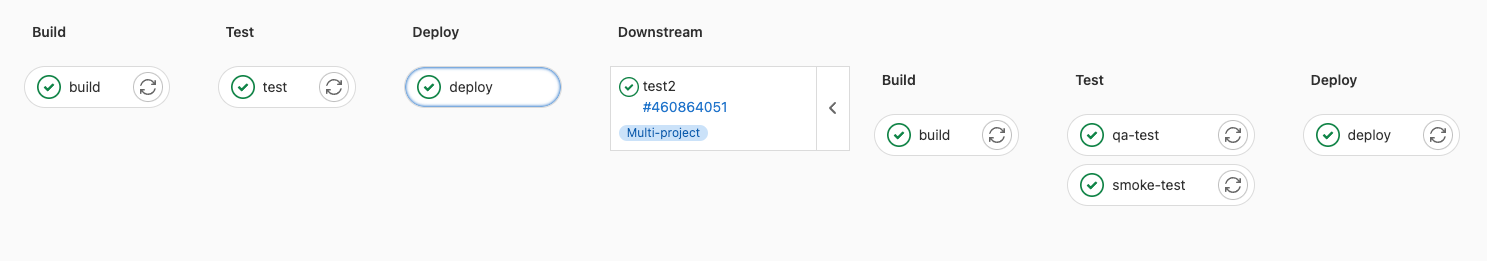

If our app spans across different repositories, we should instead leverage multi-project pipelines. Each repository defines a pipeline that suits the project's needs. Then, these standalone and independent pipelines can be chained together to create essentially a much bigger pipeline that ensures all the projects are integrated correctly.

There can be endless possibilities and topologies, but let's explore a simple case of asking another project

to run a service for our pipeline.

The app is divided into multiple repositories, each hosting an independent component of the app.

When one of the components changes, that project's pipeline runs.

If the earlier jobs in the pipeline are successful, a final job triggers a pipeline on a different project, which is the project responsible for building, running smoke tests, and

deploying the whole app. If the component pipeline fails because of a bug, the process is interrupted and there is no

need to trigger a pipeline for the main app project.

The component project's pipeline:

build:

stage: build

script: ./build_component.sh

test:

stage: test

script: ./test_component.sh

deploy:

stage: deploy

trigger:

project: myorg/app

strategy: depend

The full app project's pipeline in myorg/app project:

build:

stage: build

script: ./build_app.sh # build all components

qa-test:

stage: test

script: ./qa_test.sh

smoke-test:

stage: test

script: ./smoke_test.sh

deploy:

stage: deploy

script: ./deploy_app.sh

In our example, the component pipeline (upstream) triggers a downstream multi-project pipeline to perform a service:

verify the components work together, then deploy the whole app.

A programming analogy to multi-project pipelines would be like calling an external component or function to

either receive a service (using strategy:depend) or to notify it that an event occurred (without strategy:depend).

Key differences between parent-child and multi-project pipelines

As seen above, the most obvious difference between parent-child and multi-project pipelines is the project

where the pipelines run, but there are are other differences to be aware of.

Context:

- Parent-child pipelines run on the same context: same project, ref, and commit SHA.

- Multi-project pipelines run on completely separate contexts. The upstream multi-project pipeline can indicate a ref to use, which can indicate what version of the pipeline to trigger.

Control:

- A parent pipeline generates a child pipeline, and the parent can have a high degree of control over what the child pipeline

runs. The parent can even dynamically generate configurations for child pipelines. - An upstream pipeline triggers a downstream multi-project pipeline. The upstream (triggering) pipeline does not have much control over the structure of the downstream (triggered) pipeline.

The upstream project treats the downstream pipeline as a black box.

It can only choose the ref to use and pass some variables downstream.

Side-effects:

-

The final status of a parent pipeline, like other normal pipelines, affects the status of the ref the pipeline runs against. For example, if a parent pipeline fails on the

mainbranch, we say thatmainis broken.

The status of a ref is used in various scenarios, including downloading artifacts from the latest successful pipeline.Child pipelines, on the other hand, run on behalf of the parent pipeline, and they don't directly affect the ref status. If triggered using

strategy: depend, a child pipeline affects the status of the parent pipeline.

In turn, the parent pipeline can be configured to fail or succeed based onallow_failure:configuration on the job triggering the child pipeline. -

A multi-project downstream pipeline may affect the status of the upstream pipeline if triggered using

strategy: depend,

but each downstream pipeline affects the status of the ref in the project they run. -

Parent and child pipelines that are still running are all automatically canceled if interruptible when a new pipeline is created for the same ref.

-

Multi-project downstream pipelines are not automatically canceled when a new upstream pipeline runs for the same ref. The auto-cancelation feature only works within the same project.

Downstream multi-project pipelines are considered "external logic". They can only be auto-canceled when configured to be interruptible

and a new pipeline is triggered for the same ref on the downstream project (not the upstream project).

Visibility:

- Child pipelines are not directly visible in the pipelines index page because they are considered internal

sub-components of the parent pipeline. This is to enforce the fact that child pipelines are not standalone and they are considered sub-components of the parent pipeline.

Child pipelines are discoverable only through their parent pipeline page. - Multi-project pipelines are standalone pipelines because they are normal pipelines, but just happen to be triggered by an another project's pipeline. They are all visible in the pipeline index page.

Conclusions

Parent-child pipelines inherit a lot of the design from multi-project pipelines, but parent-child pipelines have differences that make them a very unique type

of pipeline relationship.

Some of the parent-child pipelines work we at GitLab will be focusing on is about surfacing job reports generated in child pipelines as merge request widgets,

cascading cancelation and removal of pipelines as well as passing variables across related pipelines.

Some of the parent-child pipeline work we at GitLab plan to focus on relates to:

- Surfacing job reports generated in child pipelines in merge request widgets.

- Cascading cancelation down to child pipelines.

- Cascading removal down to child pipelines.

- Passing variables across related pipelines.

You can check this issue for planned future developments on parent-child and multi-project pipelines.

Leave feedback or let us know how we can help.

Cover image by Ravi Roshan on Unsplash